Anatomy reimagined: Evolution of the anatomy lab

At Mayo Clinic, the study of anatomy is more than just dissection — and it’s for more than just medical students.

It’s 2015 in the clinical anatomy laboratory at Mayo Clinic, and first-year Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine students are opening their cadaver tables for the first time.

They find the cadaver lying face down, covered in towels and protective sheeting. Soon it’s time to uncover the back and make their first incision.

“That first cut is the most difficult to make because you shy away from it, you’re nervous, you don’t want to mess up,” then-medical student Nate Vinzant, M.D. (MED ’19, I ’20, ANES ’23, CANS ’24), says in the 2018 documentary “The First Patient,” which follows a class of Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine students and teaching assistants as they spend seven weeks in the anatomy lab.

But soon enough, “The First Patient” shows the students gain confidence and the lab becomes a busy hive of activity. Students describe the buzzing of saws, the bright lights, the smell of formaldehyde and the constant tension in the air as everyone tries “to learn as much as they can in as little time as they can about everything that they can,” as one student puts it. There’s a constant hum of discussion as students work together to decode the intricacies of the human body.

“Is this actually a thing?” one student asks.

“You think that’s the thoracic duct? You sure about that?”

“Gee, this isn’t normal size,” one student says. “What in the world? That is crazy!” another exclaims in response.

“We may have cut through it.” “We might have, yeah.”

It’s a scene familiar to medical professionals across generations, as novice-led cadaver dissection has long been considered the gold standard of medical student anatomy education and a rite of passage for future physicians.

But if a documentary crew filmed an anatomy course in the clinical anatomy laboratory at Mayo Clinic today, they would find a different scene. Students interact with the human body in many ways, using multiple resources and technology — including ultrasonography, enhanced videography, 3D printing, virtual reality and more — but no longer engage in novice-led dissection.

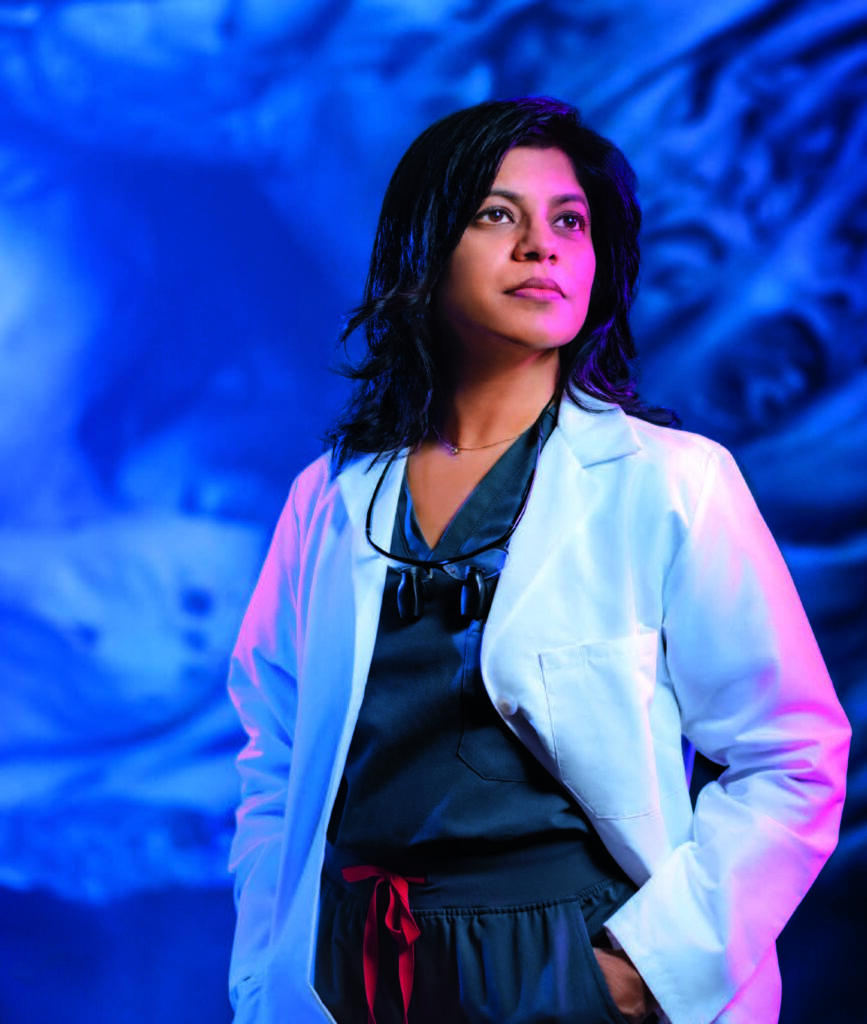

Nirusha Lachman, Ph.D. (ANAT ’07), chair of the Department of Clinical Anatomy at Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, says these changes have enhanced students’ experience and opportunities for learning anatomy at Mayo Clinic.

“Cadaveric dissection is a trusted method for learning anatomy but is most effective when used by the right learner at the right time. It’s just one of many tools for learners and trainees at all levels to study the human body,” Dr. Lachman says. “There is only one gold standard for understanding anatomy: the human body — whether that comes from the patient, the donor or material that has been imaged.”

And if documentarians wanted to get a full grasp on how anatomy is used at Mayo Clinic, they would have to venture outside of gross anatomy class. In fact, they could collect hours of footage of trainees, physicians and researchers working in multidisciplinary teams with clinical anatomists to innovate and answer pressing clinical and research questions.

“There is a misperception that anatomy is only for the first-year medical student,” says Dr. Lachman. “In the Department of Clinical Anatomy, we have broken away from tradition — both in how we approach education and how we expand our understanding of anatomy.”

A NEW VIEW

Though many of the recent changes to anatomy education at Mayo Clinic were part of the clinical anatomy department’s long-term strategy, some of them were realized sooner than anticipated.

With the advent of COVID-19, the department worked quickly to implement an existing strategy for a hybrid learning platform. It would be easy to assume these changes resulted in a lower-quality student experience; across the country, many teachers at all educational levels had to make do with clunky video-conferenced classes.

But at Mayo Clinic, anatomy instructors successfully transformed a hands-on experience to a hands-off, virtual curriculum in real time, utilizing technologies like radiology, ultrasonography, 3D printing and virtual reality.

The traditional anatomy classroom was physically redesigned to allow for a team-based, immersive education experience. That included the intro- duction of a laboratory-based studio, staffed with full-time videographers and photographers working as the department’s designated anatomical content capture specialists.

“How many of you stood around that cadaver in first year and agreed that you were seeing what your instructor was pointing at, even though you really didn’t? You have 10 people around the cadaver and the instructor says, ‘Here is the recurrent laryngeal nerve.’ And students say, ‘Yes, yes, recurrent laryngeal nerve,’ despite having a less-than-adequate view or a very short time to view it,” Dr. Lachman says.

In the clinical anatomy studio, instructors teach and dissect while content capture specialists provide targeted shots and views using a combination of overhead, hand-held and endoscopic cameras that are projected onto large screens in the lab. This means every student has the same high-definition, immersive view of the anatomy.

The studio also has the capacity to transmit video and images around the world. Additionally, livestreams are recorded and made available to all Mayo Clinic learners and trainees. These recordings can be rewatched later or loaded into a virtual reality headset, supporting the department’s experiential learning strategy.

“Some people listen to learn. I read. Some people want to see the visual, some people want to go into that VR space. Anything we capture can be imported into an Oculus headset, so you can feel like you’re walking through the posterior mediastinum, for example, if you want to,” Dr. Lachman says. “The most important thing is that you want to provide people with many opportunities to interact with anatomy.”

Anatomists through the ages have improved their craft with improving technology, Dr. Lachman says, utilizing drawing, block printing, photographs, atlases, video atlases — and today, virtual reality, 3D printing and more — to capture the human body.

“The issue is always one of: How do we use new-world technology to elevate an old-world subject?” she says. “I think I would be remiss as a clinical anatomist not to try to leverage the technology that we have to present anatomy in a way that becomes better and more meaningful.”

NOT FOR THE NOVICE

Along with the laboratory studio, the hybrid learning environment facilitated another significant change to anatomy education at Mayo Clinic: Instead of novice-led dissection, medical students now participate in learner-driven, prosection-based education.

The use of prosection is neither new nor innovative, and both dissection and prosection are proven, effective tools for learning anatomy, Dr. Lachman says. But some argue that dissection experience is superior, believing it translates to dissection skill and deep anatomic knowledge. In popular perception of novice-led dissection, students arrive in the anatomy lab timid, squeamish pupils, and after weeks of carefully carving their way through the complete cadaver, they emerge toughened, proven physicians.

The reality is more complicated. It’s true that some people love their dissection experience and benefit from the “humanistic value that actually interacting in the anatomy, the body, brings to you,” Dr. Lachman says. But she believes that for most people, the traditional anatomy course doesn’t adequately inform later clinical practice. Students with minimal anatomy knowledge and no dissection experience are expected to adequately and completely dissect a cadaver in just a few weeks.

“Dissection is not the best tool for novice learners,” Dr. Lachman says. “It takes many hours of dissecting and a solid theoretical and clinical under- standing of anatomy to be able to effectively learn through dissection.”

Today, Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine students can take an anatomy selective using prosected donors after they’ve completed their first-year anatomy course. Those who want more exposure to dissection can serve as teaching assistants, and those entering specialties that benefit from a strong knowledge of anatomy can take a fourth-year anatomy elective that focuses on their clinical specialty of interest.

Regardless of whether a student chooses to dissect, the goal for every student is the same, Dr. Lachman says: “constant engagement with anatomy” through multiple modalities.

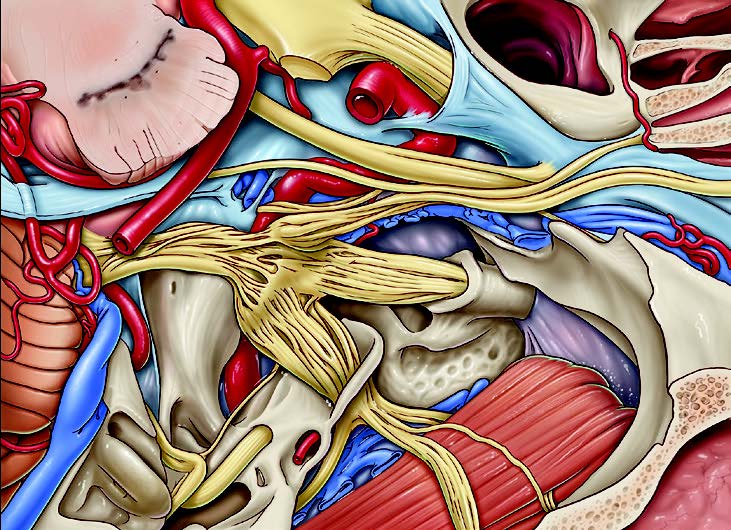

A lateral overview of the middle cranial fossa and its contents created by Mayo Clinic senior medical illustrator Steven Graepel, M.A., in collaboration with Mayo Clinic neurosurgeon Maria Peris Celda, M.D., Ph.D.

Various 3D-printed models allow Mayo Clinic learners to touch and see accurate anatomical representations.

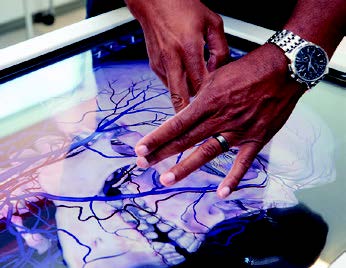

A simulation operations specialist demonstrates use of the Anatomage virtual dissection table in the J. Wayne and Delores Barr Weaver Simulation Center at Mayo Clinic in Florida.

ANATOMY FOR ALL

Like most other academic medical centers, Mayo Clinic’s clinical anatomy department historically focused on educating medical students. Today, that’s just a fraction of what the department does.

Of the approximately 250 donors that the Mayo Clinic body donation program receives each year, about eight or fewer are used in the medical school curriculum, says department administrator Jonathan Torrens- Burton. Some of the rest support health science education, residency education and research, but most support the practice — a reality reflected in the department’s official name change from the Department of Anatomy to the Department of Clinical Anatomy.

“As a Department of Clinical Anatomy, our mission is to transform patient care through education, research and practice innovation,” Dr. Lachman says.

The department wants to use its anatomical knowledge, imaging and donor materials to help Mayo Clinic physicians better understand patients’ often-complex anatomy and how that anatomy relates to clinical outcomes.

For example, when physicians devised a new tool to conduct a minimally invasive approach to carpal tunnel release, they partnered with the Department of Clinical Anatomy to test it on cadavers, improving the procedure and the tool in the process.

The department also assisted Samir Mardini, M.D. (PLS ’06), leader of the team that successfully performed Mayo Clinic’s first-ever face transplant. Dr. Mardini is the chair of the Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. Dr. Mardini and his team spent countless weekends and weekdays in the clinical anatomy lab simulating the entire face transplant procedure and gaining a better under- standing of the intricate anatomy of the face, including the entire bony structure, muscles, arterial and venous branches, and nerves that provide feeling and movement.

“Without the ability to collaborate with our incredible colleagues in the Department of Clinical Anatomy, the face transplant would not have been possible,” says Dr. Mardini.

The Department of Clinical Anatomy and Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery continue to work together on many innovative projects to restore function with facial reconstruction.

The Department of Clinical Anatomy also wants to be as responsive as possible to clinical needs. For example, surgeons operating on a patient with complex congenital heart disease may only have a day or two of lead time to prepare for a procedure. They can call the Department of Clinical Anatomy and get immediate access to donor material and images or even perform dissections before the surgery.

“Anatomical variations that are patient-specific can impact clinical outcomes,” Dr. Lachman says. “This is an area of immense opportunity for interpreting patient anatomical data.”

“ We have broken away from tradition — both in how we approach education and how we expand our understanding of anatomy.”

Nirusha Lachman, Ph.D.

KEYS TO THE KINGDOM

Though the department has recently emphasized partnering with the practice, it has long been working with Mayo Clinic physicians, allied health providers and students.

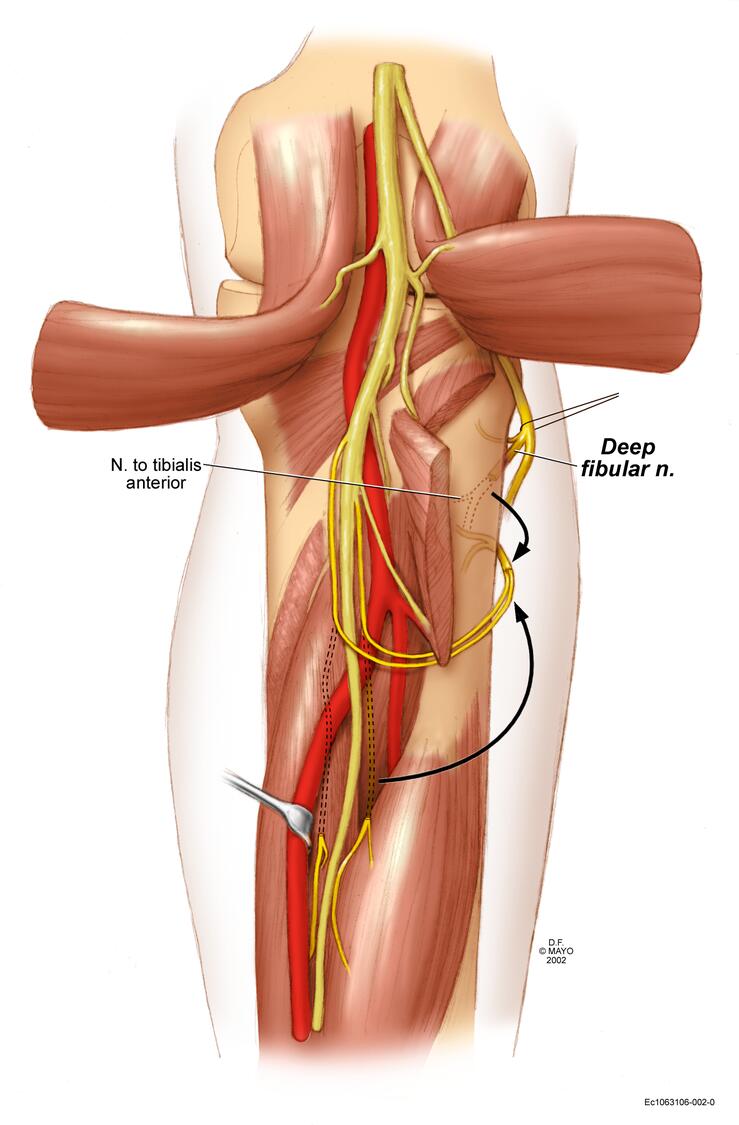

When Kale Bodily, M.D. (MED ’05, RD ’10), was a Mayo Clinic medical student taking gross anatomy in the 2000s, Robert Spinner, M.D. (MED ’89, NS ’00), a consultant in the Department of Neurologic Surgery and the Burton M. Onofrio, M.D., Professor of Neurosurgery, visited the class and gave a presentation on nerve transfers in the upper extremities to treat certain types of peripheral nerve injuries.

“They did a great job in that program of providing clinical correlation to help us see the relevance of what we were learning,” Dr. Bodily says.

Later, when Dr. Bodily’s anatomy class progressed to dissecting the lower extremities, he wondered: Was anyone doing nerve transfer surgeries in the leg?

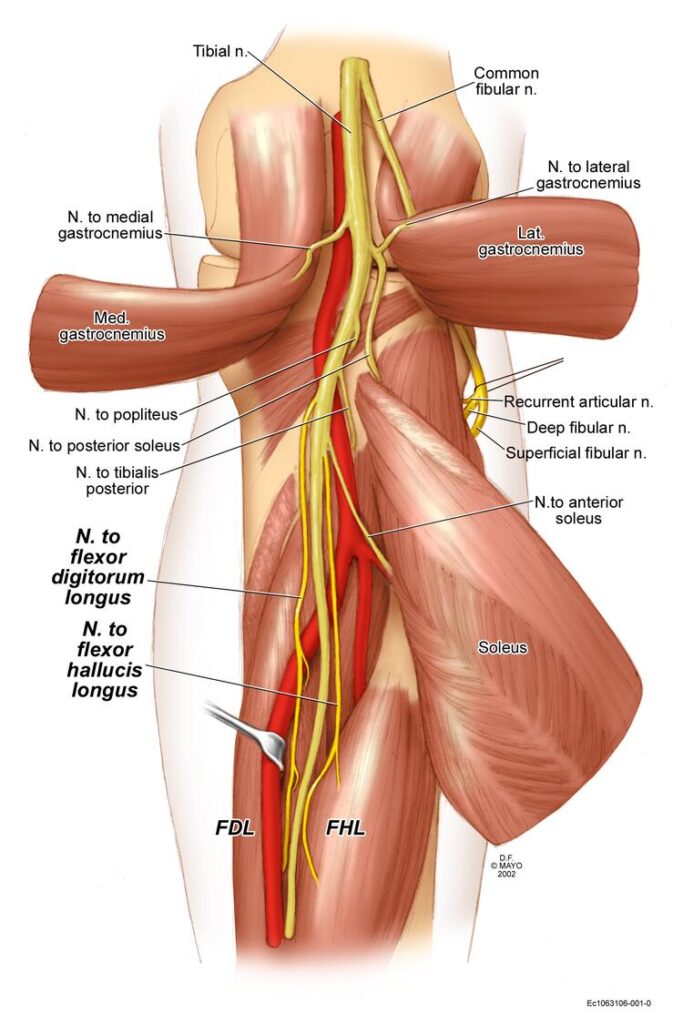

The answer was no. After discussion with Dr. Spinner and former anatomy department chair Stephen Carmichael, Ph.D. (ANAT ’82), Dr. Bodily soon found himself entrusted with 10 cadaveric legs to explore the issue. He spent hours dissecting in the evenings, characterizing and measuring the nerves and muscles in great detail, trying to determine whether the anatomy would be potentially conducive to nerve transfer surgery.

His findings were published in Clinical Anatomy alongside beautiful illustrations created by a Mayo Clinic medical artist. Eventually, Dr. Spinner began a trial of lower extremity nerve transfer procedures, with Dr. Bodily present in the operating room to lend his anatomical expertise.

“That experience was extremely unique: To get input from a world-class neurosurgeon as we were learning anatomy, and then to be curious and ask a question, and then have the strong support from an anatomy professor and a neurosurgery professor, and the resources to answer that question,” Dr. Bodily says. “It’s a great privilege to be a student at Mayo Clinic. You have the keys to the kingdom, so to speak. That applies across the board, but it applies in anatomy too.”

In Dr. Bodily’s case, his experience learning anatomy redirected his career goals.

“I was just trying to decide what kind of surgeon I was going to be, but I fell in love with all of the anatomy,” he says. “As a radiologist, I work with anatomy throughout the body every day, all day long. The clinical approach to anatomy education at Mayo Clinic had a very real impact on my career path, and I absolutely love what I do.”

LOOKING FORWARD

The Department of Clinical Anatomy is doing a lot of exciting work, but it will continue to evolve to keep up with the field — an idea that often surprises people, Dr. Lachman says.

“People say, ‘What in anatomy has changed? Anatomy is anatomy,’” Dr. Lachman says. “Our knowledge of anatomy and our capacity to apply it in clinical practice is dependent on asking the right questions and enhanced by engaging in different views of what we already know.”

As Mayo Clinic continues to translate anatomical knowledge from the bench to the bedside and back, she says, the subject of anatomy remains relevant and alive.

This story appears in the latest issue of Mayo Clinic Alumni magazine. You can read or download a PDF of the issue here.

Mayo Clinic alumni are entitled to the print version of the quarterly magazine. If you’re not receiving the magazine, register or log in to your online MCAA profile to make sure your address is correctly entered. Or contact the Alumni Association at mayoalumni@mayo.edu or 507-284-2317 for help.

Credit: Vintage anatomical drawings by Eleanora Fry; mixed media illustrations by Martin O’Neill. Learn more about Eleanora Fry, one of Mayo’s earliest medical illustrators here.