Medical Care, Chapels, and Challenges: Growing up at the Grand Canyon, by Paul Leo Schnur, M.D. (S ’70, PLS ’72)

(Originally published in Reflections of Grand Canyon historians : ideas, arguments, and first-person accounts, a monograph based on talks given at the 2nd Grand Canyon History Symposium, held Jan. 25-28, 2007 at Grand Canyon National Park. Edited by Todd R. Berger.)

You lived where? What were you doing there? I hear these questions often when in conversation with new acquaintances and I tell them I grew up at the Grand Canyon. The following is my story.

I was young when our family moved to Grand Canyon Village in the 1940s. We had moved often because my dad, Leo, was a doctor for the Indian Service, and he had been stationed on several reservations before World War II. After his service as a medical officer in the military, we moved to several more reservations and then to the Grand Canyon. For me, the transition was just another move, another school, and more new friends. I was in the seventh grade. Little did I know how much of a culture change it would be.

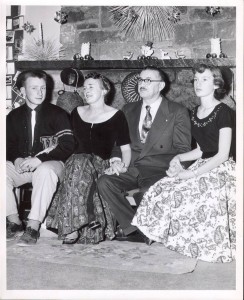

Paul Schnur, M.D. (second from left), with parents Dr. Leo Schnur and Aileen and sister Sally Schnur Forster at their home in Grand Canyon in 1948.

Recently while I was researching a history project in the Sharlot Hall Museum in Prescott, Arizona, I found out considerably more detail about why we moved to the canyon than I had known. While reading the book, Mile Hi Docs, by Melvin W. Phillips, MD, my eye caught the chapter titled, “We Arrive at the Grand Canyon.” In fall 1948 after a residency and two years in the army, Dr. Phillips and his wife traveled to the Grand Canyon to interview for the position of physician at the Grand Canyon Hospital. Dr. Coville, the hospital’s doctor at that time, was about to leave. Dr. Phillips was offered the job but learned that residents of Grand Canyon Village, which was within the national park, were not allowed to keep pets. Dr. Phillips and his wife Jean had two dogs, and after much soul searching, they decided that they could not give up their pets, so they declined the offer. Dr. and Mrs. Phillips moved to Prescott, where he practiced for many years and died in 1996.

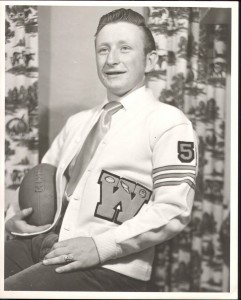

Paul Schnur, M.D. (left), with parents Aileen and Dr. Leo Schnur and sister Sally Schnur Forster at their home in Grand Canyon in 1952.

In 1945, when my dad was stationed at Sacaton, Arizona, on the Pima Indian Reservation following discharge from his army service during World War II, my parents built several homes in Oak Creek Canyon near Sedona. My mother Aileen, my sister Sally, and I spent our summers there. Dad was transferred to the Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation in Fort Yates, North Dakota, in 1946. He was active in the Republican Party and was promised a Washington, D.C., job with the Bureau of Indian Affairs if Governor Thomas E. Dewey of New York was elected president. We were packed and ready to leave for Washington when we read the change in the headlines that President Truman had been reelected. Because Mom preferred the weather in Arizona, Dad quickly began looking for a job in the Southwest. He learned of the opening at the Grand Canyon and accepted the position shortly after Dr. Phillips’s refusal. My family also had dogs, but to return to Arizona, they placed their pets with friends in Sedona.

Dr. Phillips wrote that the doctor at the Grand Canyon Hospital was paid $10,000 a year plus reasonably priced housing. My Dad, however, had a contract with the National Park Service to run the hospital and divide the profits from the practice and hospital with the park service. The hospital at the Grand Canyon, prior to my dad’s arrival, had a history of problems and a number of doctors came but did not remain long. It was built in 1931, and the first doctor was Dr. B. G. Carson. One doctor, I recall, had tried to start a nudist colony on the rim of the canyon. My dad had years of experience managing hospitals for the Bureau of Indian Affairs and soon had the hospital and practice running smoothly and profitably.

The hospital had ten beds, a clinic, a delivery room, and an operating room. A report on the hospital by Lon Garrison, the assistant park superintendent, stated that the hospital provided prepaid medical care to the employees of the park service, the Santa Fe Railway, and the Fred Harvey Company. Fee for service care was provided to tourists. The park service owned the facility and provided maintenance, and the Santa Fe Railway provided utilities. Dad provided food service, secretarial service, and nursing service. Although the hospital averaged only 30 percent full while my dad worked there, it still operated in the black. The American Medical Association, Arizona Department of Health, and Arizona and American Hospital associations approved the hospital.

Specialty backup medical care was not easy to obtain. The hospital at Flagstaff still provided quite basic care at the time. The first board-certified general surgeon in northern Arizona, Dr. Kenneth Brillhardt, began practice in Cottonwood in 1949. Phoenix was a long drive at that time before the construction of Interstate 17. Helicopters and medical evacuation planes were not in service yet. Dad, therefore, delivered babies, set fractures, performed some surgery, and took care of most emergencies. He was on call twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. During the summers, Mom, sister Sally, and I would spend our time in Sedona, and Dad would visit on the weekends. He would, however, take calls while in Sedona, and if there was an emergency at Grand Canyon or a baby to be delivered, he would drive the ninety-seven miles back to the canyon at any time of the day or night. He had a 1946 Ford Woody station wagon and would drive very fast on the open highway. Sometimes he would make the trip between Sedona and Grand Canyon several times in a single weekend. I remember one occasion when a lady in Supai was in labor and the midwife was unable to deliver the baby (it was in the breech position). My dad took one of the first helicopter rides into Havasu Canyon to deliver the baby, and because of his expertise, the mother and the baby did well. Because he had provided medical care in remote rural settings for twenty years before arriving at Grand Canyon and because of his organizational skills, he practiced very high-quality medicine. Dad would perform tonsillectomies, repair lacerations, and set fractures. Dorothy (Winter) Dunagan, his longtime nurse, told me that on one occasion a senior Fred Harvey employee developed appendicitis in the middle of the night, so Dad and Dorothy drove him in the back of the Ford station wagon to Flagstaff to have his appendix removed.

My dad, who had a high energy level, was not content to only practice medicine. He had to be involved in other endeavors and was deeply committed to Rotary, the Boy Scouts, and the construction of the Shrine of the Ages chapel. He was a president of two Rotary clubs (Grand Canyon and Sedona), and was a charter member of the latter. My dad had been a camp counselor while an undergraduate in New York City and continued his love for the outdoors by supporting the local Boy Scout troop. He was also the volunteer director of the Grand Canyon Council, which had headquarters in Flagstaff.

As I mentioned, he along with many others at the Grand Canyon, was committed to building the Shrine of the Ages chapel. He served as the first president of the Shrine of the Ages Chapel Corporation and later was named president emeritus. His colleagues on this project included Jack Verkamp, Howard Stricklin, Carl Lehnert, Walter Bimson, Governor Howard Pyle, Senator Barry Goldwater, and Fr. John Faustina, and they all became lifelong friends. (The late Fr. John Faustina performed the wedding mass for my wife, Barbara, and me and for all three of our children. He also celebrated the memorial service for my parents and Barbara’s mother.) The plan was to build the chapel on the rim of the Grand Canyon at the spot where Governor Pyle had been broadcasting the Easter sunrise service for many years. This area on the rim was called the “Shrine of the Ages.” Although the park service originally approved construction on the rim, they had a change of heart because of the impending Wilderness Bill in Congress, which was not passed until September 1964. Consequently, the chapel was built on its present site, back from the rim.

It was an out-of-the-ordinary lifestyle for a young boy. The fact that families could not have pets was quite unusual, as most children wanted them. I recently attended the 100th anniversary celebration of the founding of Montezuma Castle National Monument. Theodore and John Cook spoke of their move from the Grand Canyon in 1950 when their father took over as superintendent of Montezuma Castle. They prayed that after leaving the canyon they would be allowed to have pets.

As in many rural communities, the Grand Canyon School was small. It was built in 1939. The previous school was converted to the park service naturalist’s workshop and was very close to our home. There were two classes in each room in my school, which had grades one through eight. Because there were only eight grades, the students had to leave home to attend high school. I attended Judson School in Scottsdale for ninth grade but then transferred to Wasatch Academy in Mt. Pleasant, Utah. Most high school students from Grand Canyon attended this school. In those days because most national parks did not have a high school, there were students at Wasatch from many of the western national parks. John (Tersh) Verkamp reminded me, during the occasion of the 100th birthday celebration in 2006 of the Verkamp’s store, that a Grand Canyon High School was started the year after he graduated eighth grade in 1954. There were eight students in my eighth-grade graduating class and most of us eventually attended Wasatch Academy. We have remained lifelong friends. Attending Wasatch was a transportation challenge. We would travel to and from Wasatch by Greyhound bus. We would catch the bus at Cameron late in the night and, twelve long hours later, arrive in Mt. Pleasant. We would take that bus ride to school in the fall and then return for Thanksgiving, Christmas, and spring break.

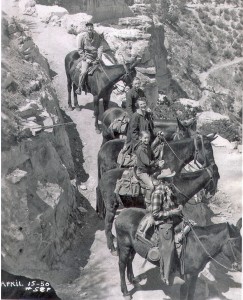

At the canyon there were numerous activities for young people. The Boy Scouts were exciting for me as a child. We did a lot of hiking and camping. Hiking trips were not only along the rim but also into the inner canyon and Havasu Canyon. In the winter we enjoyed sledding down the hill in front of our house on Navajo Street, which was located across the railroad tracks from El Tovar Hotel. The road was usually covered with packed snow in winter. There was one area that was always clear of snow because a steam pipe traversed the road underground. We cross-country skied alongside the road on East Rim Drive (Desert View Drive today). Accompanied by adults, we would often go downhill skiing at the Williams or Flagstaff ski areas. On one sad occasion while skiing at the Williams ski area, one of our classmates, Erik Garrison, was killed when he caught his sleeve in a pulley of the rope lift. That was a very sad time for the entire village. The grade school was closely connected to the community.

While the Shah of Iran was visiting the Grand Canyon on November 29, 1949, he wanted to visit a school. He and his wife visited our class. Before he arrived, our teacher, Mrs. Omar C. Heitmeyer, briefed us on all things Iranian. She placed a large map of the world in front of the room. The first question the shah asked was if anyone could show him on the map where Persia was located. When we could not locate that country, Mrs. Heitmeyer quietly said to the shad, “I believe our children know your country by the name of Iran.” At that statement we all raised our hands.

I remember when the identical twins Harly and Charley Marquis entered the first grade. Their family had lived in the bottom of the canyon until they were school-age. Because they had lived in a remote area prior to school, they did not speak English. They spoke a language that they had invented. Their mother was the only one able to understand them.

When I was in grade school I wore braces. There were no orthodontists in northern Arizona. My parents took me to Phoenix for the braces. They had to be tightened every two weeks, so I would ride the train alone to and from Phoenix for that treatment. I left Grand Canyon at 8:00 PM on the train and arrived two hours later in Williams. I then caught the Super Chief from Williams to Ash Fork and changed trains again. I would board the Phoenix-bound train, which left about 3:00 AM, and I arrived in Phoenix about 8:00 AM. I rode the city bus to downtown Phoenix, got my braces tightened, saw two double-feature movies, rode the bus back to the Phoenix train station, and boarded the train for the return trip to the canyon. That was my routine every other week for two years. Would you allow your seventh-grade son to do that today?

I stayed in touch with many of my friends from my years at the Grand Canyon. My friend Eric Ramsey was sent to Vietnam by the State Department and was captured by the Vietcong. He was held captive in tiger cages for five years. Another great friend was the late Phil Weeks. He and I graduated from grade school, high school, and college together. We were the best man in each other’s weddings. I recall that during high school, we would come home for Christmas break and ask our fathers if we could drive their cars. In the winter, in those days, East Rim Drive was closed so that the park service did not have to plow the roads. Phil and I would drive past the barriers and out to the rim. We would then drive to the lookout point parking lots and spin and skid the cars. It was great fun, and we sure learned how to drive in the snow. Because there was no damage to the cars, our fathers never knew about this. The Verkamp children were younger, but our families spent a lot of time together enjoying parties, picnics, and trips to Sedona. We had a great time swimming and fishing at our home, Bedside Manor, in Oak Creek Canyon.

During my years at Grand Canyon, one could walk or ride a bike anywhere in the village, which is still largely true today. I had a paper route when I was in grade school. Sounds normal, but there were no paper deliveries in Grand Canyon Village at that time. A bus from Phoenix arrived about midafternoon and brought the Arizona Republic and other papers. They were delivered to the newsstand at El Tovar Hotel and the Bright Angel Lodge. The paperboy would take orders for the papers and purchase them. He would then deliver them by bicycle after school to the customers’ homes. As was customary, when I left for high school, I passed the route on to someone else. Another job I held while in grade school was setting pins in the bowling alley at Rowe Well, which no longer stands today. After several months and several injuries caused by balls thrown by tipsy bowlers, my dad persuaded me to resign from that job.

There were always summer jobs for the local young people. Because the Grand Canyon tourist business was seasonal, many would be hired during the summer. When I was in high school, I worked at the gas station, which was located down the hill from the school. Later I worked at the laundry folding sheets.

When I was in grade school and high school, my career choice was to become a photographer. Virgil Gibson, the photographer for the Fred Harvey Company and friend of my parents, gave me a job in Lookout Studio developing photographs and selling curios. I would accompany him on photographic jobs and carry his equipment. On one occasion, we were sent to meet the morning train because a dignitary was coming to the canyon by private car. His arrival was a secret, but the Fred Harvey Company wanted photographs of him because he was to be a guest at El Tovar Hotel. Virgil and I met the train. The dignitary was General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Virgil and I had the opportunity to get some wonderful photos of him. It was my pleasure to meet him. Soon after his visit, he was elected president.

When I was in high school, I managed Kachina Lodge on West Rim Drive, today’s Hermit Road. The lodge, which is no longer in existence, was on the Orphan Mine property. It had a restaurant, curio shop, and bar in addition to lodge rooms, cabins, and tents. Kachina Lodge had previously been called “The Rogers Place.” It was owned by Will Rogers Jr. and managed by John Bonnell, the father of one of my eighth-grade classmates, Jon Bonnell. Jim and Ellie Barrington, from California, had purchased the lodge from Will Rogers Jr. and hired me as the summer manager. I would hire my classmates from Wasatch to work there. The mining claim reverted to the park service in 1987, and the lodge has been torn down.

After that, I worked as a bellhop at Bright Angel Lodge. For many years after my parents left Grand Canyon and while I was in college, I returned each summer to work and always found jobs for many of my college classmates. We had a grand time socializing after work because we were old enough to drink and spend evenings at Rowe Well or Tusayan. Some evenings, dances were held at Bright Angel Lodge. The tourist girls enjoyed these parties, so we had many dance partners. Because my parents had already moved, I lived in Fred Harvey Company housing. That was an experience in itself. One summer I lived in the mule wrangler dorm with the wranglers and the cooks. What I learned about life cannot be put into print.

My first cousin Bill Youngren came to live with us after he graduated from high school in 1950. He worked as a bellhop at Bright Angel Lodge and later became a desk clerk. When the Korean War started, he entered the air force. When Phil Weeks, my cousin, and I went to college in Tucson, we rented the garage apartment of the house owned by Mary Verkamp’s father, which was near the University of Arizona campus. Her father, Dr. Cornelius O’Leary, had died, but her brother Putt O’Leary lived there. After we left, some of the Verkamp kids lived there while in college. The house has since been acquired and demolished by the university.

In summer 1956, I was working as a bellhop at Bright Angel Lodge. On June 30 there was a midair collision of a TWA Super Constellation and a United Airlines DC-7 over the Grand Canyon. Paley and Henry Hudgin, brothers who ran Grand Canyon Airlines, spotted the downed aircraft. That was the worst commercial aviation accident in history at the time. Media from all over the world descended on the Grand Canyon. The center of operations was at the Red Butte Airport some fifteen miles south of the village. Most transportation at the canyon was buses or cars for the tourists, so the media people had a real problem finding rides to and from the canyon. I had a 1950 Ford and consequently made a lot of money as a personal driver for the reporters. This intense media activity lasted for several weeks and then ended as quickly as it began when on July 25 the Andrea Doria collided with the Stockholm near Nantucket, Massachusetts. The media left to cover that tragedy.

I had another interesting experience while working as a bellhop at Bright Angel Lodge. One Sunday, I was on duty when Byron Harvey Jr., president of the Fred Harvey Company, visited the Grand Canyon. He traveled by rail to Williams, where one of the Harvey cars met him and drove him to Bright Angel Lodge. The general manager of the lodge had people phone along the way as his car passed so we would know the precise time of arrival. I was with a number of employees, including the general manager and Sam Pemahinye, known as Hopi Sammie, to meet Mr. Harvey on the steps of the lodge. One of Mr. Harvey’s obsessions was immaculately clean restrooms, and it was Sammie’s job to clean those facilities and polish the copper fixtures. Soon after arrival Mr. Harvey asked Sammie to show him to the men’s room. We accompanied them. After careful inspection, Mr. Harvey complimented Sammie on the cleanliness of the restroom. Sammie replied, “Mr. Harvey, I’m mad at you.” Somewhat surprised, Mr. Harvey asked him to explain. Sammie replied that because his visit was on Sunday, his day off, the general manager had called him in to work.

While in medical school I worked with my dad in Sedona during the summer and then joined him in practice for one year after I finished my internship. Many people who lived much of their lives at the Grand Canyon moved to Sedona in retirement. Peg Verkamp, Edith Kolb Lehnert, and others built homes in Sedona and moved there later in life. The social life that they knew at Grand Canyon continued in Sedona.

I have moved many times in my life. I always enjoy returning to places I have lived to visit with longtime friends who have remained there. The one thing that is very different about the Grand Canyon is that one cannot go back and see friends. They have all left. Because there are no private homes in Grand Canyon National Park, there are usually few longtime residents. Most families spend some time working at the canyon and then move on. So when I return I experience a strange feeling. It seems that I had never lived there. No one remembers my family or me. The current residents and their friends are there only temporarily, and they too will soon be gone. Only the timeless beauty of the canyon remains.

According to an old saying, “You can never go back.” But perhaps you can. Because of gatherings like this Grand Canyon History Symposium, I got to travel back in time through my research and also reconnected with old friends.

[1] Melvin W. Phillips, Mile Hi Docs (Prescott, Ariz.: M & J Publishing, 1996), 282.

[2] Michael F. Anderson, ed., Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park (Grand Canyon, Ariz.: Grand Canyon Association, 2000), 28.

[3] Lon Garrison, “Community Endeavor Establishes Modern Hospital at Grand Canyon,” Arizona Republic, June 1, 1952.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Dorothy (Winter) Dunagan, personal communication.

[6] Anonymous, “A National Religious Shrine,” brochure for Shrine of the Ages Chapel, circa 1954. Author’s collection.

[7] Grand Canyon Grammar School Year Book, 1950, 22.