Searching for substance X

A Sherlock Holmes aficionado on the case for rheumatic relief

To say that Philip Hench, M.D. (I 1925, died 1965), was a fan of the fictional character Sherlock Holmes would be an almost laughable understatement.

Over the course of his life, Dr. Hench amassed a collection of Sherlock Holmes memorabilia that included approximately 1,800 books and hundreds of photographs, manuscripts and periodicals, including four copies of an 1887 issue of Beeton’s Christmas Annual containing the first published Sherlock Holmes story. Dr. Hench traveled to Switzerland to plead his case for a plaque honoring Holmes to be installed near Reichenbach Falls, a pivotal scene in the Holmes story “The Final Problem.” He was, as one colleague noted, “a nut on the subject.”

It’s perhaps not surprising that Dr. Hench was drawn to Holmes, says Eric Matteson, M.D. (RHEU ’89), an emeritus professor of medicine and former rheumatologist at Mayo Clinic in Minnesota who has written extensively on the history of Mayo Clinic rheumatology.

“Dr. Hench picked up on the idea that, as physicians, sleuthing for the cause of a disease or to understand a disease is a sort of Holmesian pursuit — particularly in rheumatology, where we deal with lots of very strange diseases,” says Dr. Matteson.

This Holmesian fixation may have helped fuel Dr. Hench’s own decades-long investigation to find a rheumatoid arthritis treatment — a hormone he deemed “substance X.” He eventually solved the case, making a discovery that would reshape the practice of rheumatology as well as the treatment of many diseases across medical specialties.

And yet, Dr. Hench’s contributions are just one chapter in the 100-year story of Mayo Clinic rheumatology. Dr. Hench established the practice of rheumatology at Mayo Clinic in 1926, and he was succeeded by a long line of physicians and researchers who have made their own marks on the field via cutting-edge care, robust rheumatology education and groundbreaking discoveries.

“It’s a tremendous legacy. It’s also a responsibility to uphold the standard of excellence that was set by all the people who have come before us,” says John Davis III, M.D. (I ’03, RHEU ’06, CTSA ’13), chair of the Division of Rheumatology at Mayo Clinic in Minnesota.

That includes a responsibility to continue to enhance care for people with serious and complex rheumatic diseases and to provide outstanding rheumatology training, Dr. Davis says — and to continue in the tradition of Dr. Hench and his quest to solve medical mysteries.

“We have the immense opportunity to contribute to the discovery and translation of the next diagnostic tests, approaches and cures to treat people with rheumatic diseases,” Dr. Davis says.

“THINK OF THE PAIN”

When Dr. Hench began his training and practice at Mayo Clinic in the 1920s, rheumatic diseases were as formidable a villain as the slippery Holmes nemesis Moriarty.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) — known at the time by various names including chronic infectious arthritis — was a relentless, progressive disease with no curative treatments. According to Dr. Hench, the prevailing attitude of many physicians toward rheumatic diseases was pessimism. But Dr. Hench was dedicated to the field and explained that he was motivated by the millions of Americans with rheumatism and arthritis, writing, “Think of the pain, disability, frustrated hopes and economic loss!”

In 1926, Dr. Hench was tapped to establish a rheumatology service for patients with chronic arthritis at Saint Marys Hospital in Rochester, Minnesota, serving patients with serious joint problems — usually multiple swollen, painful joints.

These patients were primarily treated with bed rest and physical therapy exercises, along with some analgesics for pain such as aspirin. More experimental approaches were also attempted at Mayo Clinic throughout the 1930s and 1940s, many of which were based on the belief that RA stemmed from a chronic infection. These included vaccine therapy, inducing fevers in patients and gold salt injections; none resulted in significant, sustained relief of symptoms.

THE GAME IS AFOOT

In 1929, Dr. Hench came upon his first clue that would lead to a more effective RA treatment. He observed that jaundiced patients often experienced swift improvement in their RA symptoms.

“Only one conclusion was possible,” Dr. Hench wrote. “Contrary to the belief of centuries, rheumatoid arthritis must be potentially reversible, and rapidly so.”

Dr. Hench tried giving “various products of the liver” to arthritic patients, but these experiments had no apparent effect on the disease. Then Dr. Hench witnessed the same rapid relief of RA symptoms in pregnant women.

“We began to suspect that the mysterious substance was neither a product of the liver nor a female hormone but might be a steroid hormone common to both men and women,” Dr. Hench wrote. “But what hormone?”

Dr. Hench and his colleagues tried all sorts of experimental treatments for RA, including transfusing blood from jaundiced patients, administering female hormones and inducing jaundice.

Eventually, Dr. Hench knew that he “very much needed chemical help,” he wrote.

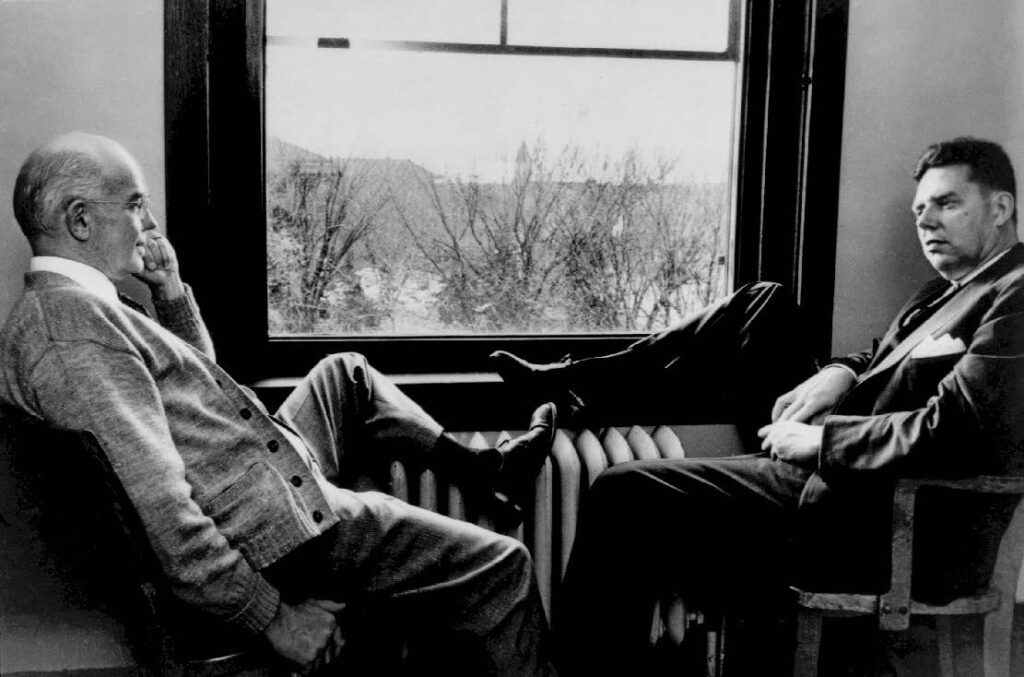

This help would come from a Mayo Clinic scientist who worked just a few meters away from Dr. Hench. By 1938, biochemist Edward Kendall, Ph.D. (BIOC 1914, died 1972), would become Dr. Hench’s chief collaborator on the path to rheumatic treatments. Sherlock had found his Watson.

A CHEMICAL SO COMPLEX

Even with the combined efforts of Drs. Hench and Kendall, success did not come easily.

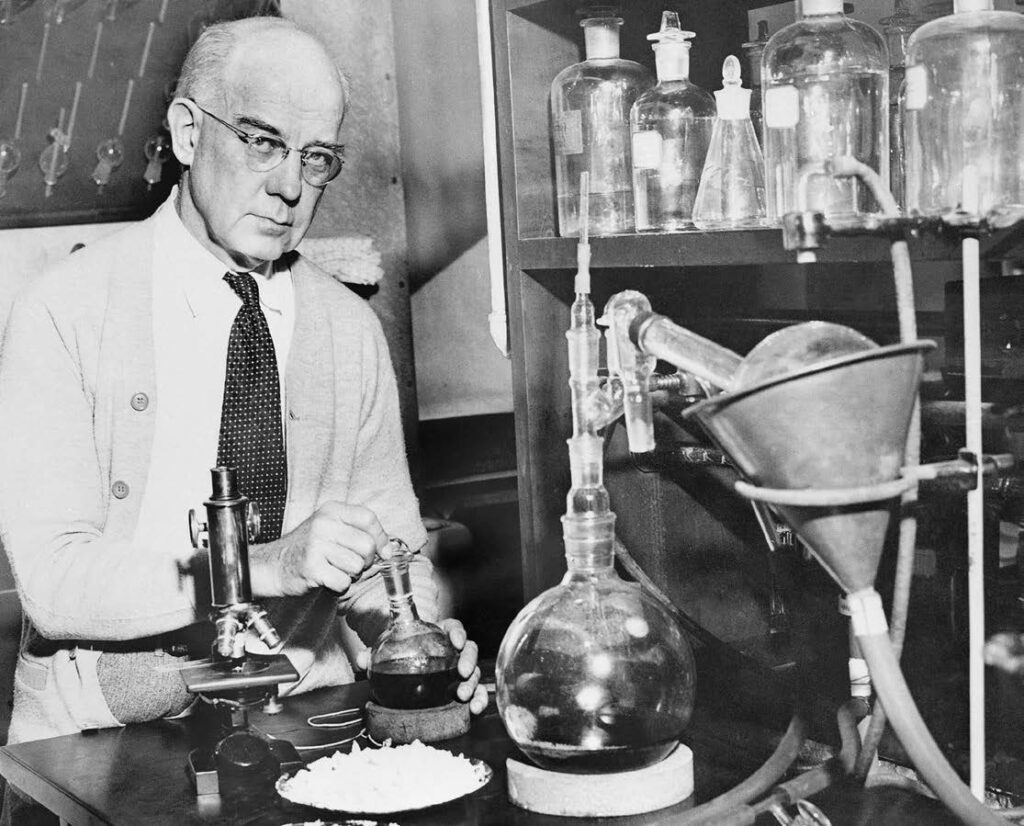

Dr. Kendall’s main aim was to isolate, identify and synthesize the hormones of the adrenal cortex. This effort put Dr. Kendall and his team in fierce competition with scientists around the world and made him “intensely preoccupied with a problem which at first seemed remote from ours,” Dr. Hench wrote.

By his own account, Dr. Hench’s confidence in his ability to solve the case of substance X wavered over the years. But it would turn out that their suspect was hiding in plain sight — within Dr. Kendall’s adrenal work.

Of the 28 adrenal cortex hormones scientists isolated, preclinical testing showed that only a handful might have physiological potency. Dr. Kendall named these compounds A, B, E and F. But to test these compounds in a clinical trial, they would need to be synthetically created, as it was extremely challenging and costly to isolate them from animal adrenal glands.

“This was the most difficult part of all, because no chemical so complex had ever been made by man,” Dr. Hench wrote. “The only ones bold enough to begin and continue the task were Kendall and his associates in Rochester and the research chemists of Merck & Company.”

It took five years to create a synthetic compound A, via a 38-step process. In the end, the synthetic product failed as a treatment for Addison’s disease, leading to bitter disappointment.

But the group learned from compound A, tried again and created a synthetic compound E. Compound E did benefit patients with Addison’s disease, but the disease was not common enough to make this a profitable venture for Merck.

“At this point, [Merck associates] were men with a substance (compound E) hunting for some unknown condition which it might affect, while I remained a man with certain diseases hunting for an unknown compound (substance X) which might affect them,” Dr. Hench wrote.

A MEDICAL MIRACLE

By this time, Dr. Hench thought that substance X might be found in the adrenal gland. So, he wrote to Merck, requesting some remaining compound E to experimentally treat an RA patient. In 1948, the compound was injected into a volunteer Mayo Clinic patient; she experienced marked relief of her symptoms in just a few days.

Excited by these results, Dr. Hench’s colleagues Charles Slocumb, M.D. (I ’35, died 1996), and Howard Polley, M.D. (I ’43, died 2001), treated additional patients with moderately severe or severe RA. All patients who received compound E again experienced significant improvement in symptoms. The resulting seminal publication reporting the results in 14 patients was published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings in 1949.

Dr. Hench then invited five prominent physicians to Mayo Clinic to observe a clinical demonstration of the effects of compound E, including Richard Freyberg, M.D., then-president of the American Rheumatological Association.

“During the course of two days, we watched them miraculously improve. Within 24 hours, we saw a generalized effect from the compound that led one to say, ‘I never felt so well during the time that I’ve had arthritis as I do now,’” Dr. Freyberg said in a 1998 interview.

Dr. Hench reported these results in 1949 at the Seventh International Congress of Rheumatic Diseases in New York City to fervent enthusiasm, thunderous applause and even a rush of physicians to the stage to congratulate him.

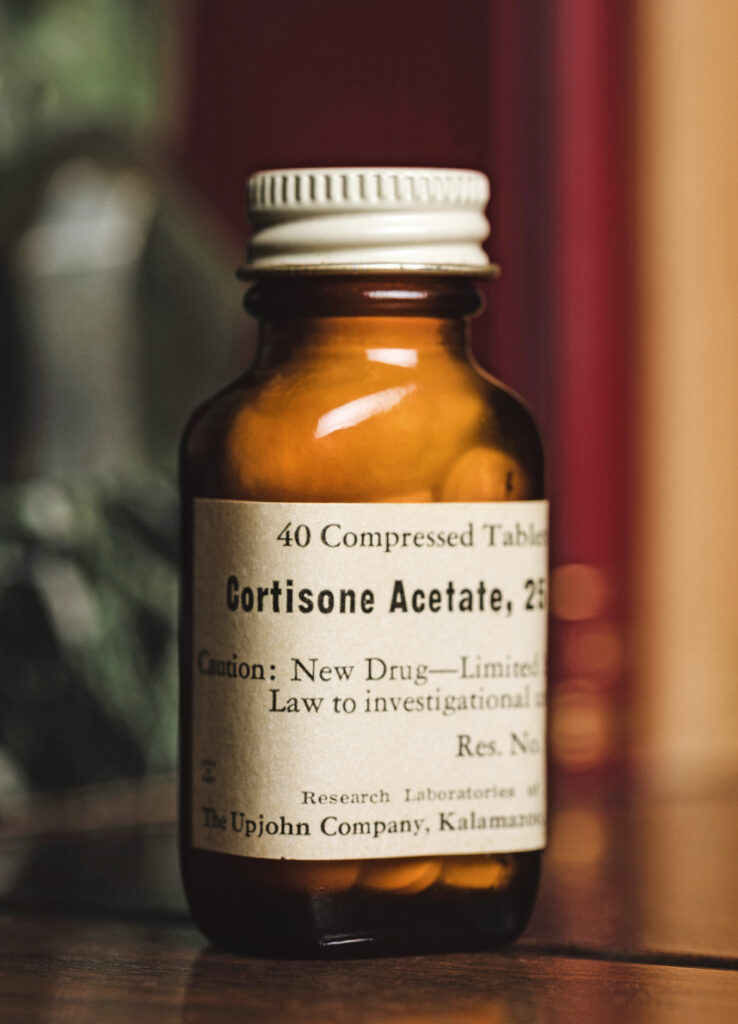

Drs. Hench and Kendall won the 1950 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work, alongside a Swiss physician, Tadeus Reichstein, M.D., who had independently isolated compound E. Drs. Hench and Kendall would give compound E its name: cortisone.

Edward Kendall, Ph.D., in his laboratory at Mayo Clinic. Dr. Kendall’s work on the hormones of the adrenal complex proved pivotal in the search for rheumatoid arthritis treatment.

ADVERSE EFFECTS

Cortisone was then used successfully as a treatment for lupus, vasculitis, psoriatic arthritis, allergies, skin diseases and many other conditions; substance X was lauded as a wonder drug.

But it was clear from early use that cortisone could result in adverse effects like hypertension, weight gain, anxiety, and even gastrointestinal ulcers, hypomania and psychosis.

Dr. Freyberg recalled witnessing Dr. Hench receive a distressing call from one of the first RA patients to receive compound E. The call came before Dr. Hench’s presentation at the 1949 New York meeting.

“Between sobs she told how miserable she was, feeling persecuted, suffering delusions and unable to sleep,” Dr. Freyberg said in 1998. “This phone call had a profound effect on Dr. Hench. Before I knew it, he was crying, ‘What have I done to this patient?’ I am convinced that this phone call influenced the tone of his presentation that day. He cautioned the listeners to be alert for toxic effects, calling for careful scrutiny of patients and their complaints after they had received the drug.”

Dr. Hench had solved the case of substance X. In doing so, he and Dr. Kendall had provided important relief for a range of diseases inside and outside of rheumatology.

But in addition to its many troubling side effects, cortisone could not cure or modify RA. In 2007, a Mayo Clinic article by Angel Gonzalez, M.D. (CLRSH ’06), et al. found that survival rates of patients with RA hadn’t increased in four decades — despite improved mortality rates in the general population.

“ The arrival of DMARDs moved RA treatment from just making people feel better today to changing their disease trajectory.”

– Elena Myasoedova, M.D., Ph.D.

BACK ON THE CASE

Over the decades, other physicians and researchers pursued their own suspects for effective RA treatment. In the 1980s, some answers began to emerge in the form of inflammation-blocking pharmaceuticals that would come to be known as disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). These drugs can slow progression of RA, reduce the risk of comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and lead to improved mortality outcomes.

“The arrival of DMARDs moved RA treatment from just making people feel better today to changing their disease trajectory,” says Elena Myasoedova, M.D., Ph.D. (HSR ’10, I ’16, RHEU ’19, CTSA ’19). “DMARDs help to reduce the inflammation at its source, preventing joint damage and helping people to keep their mobility and independence much longer.”

But DMARDs come with their own various risks and side effects, and patients may go through a lengthy process of medication trial and error to find the right fit.

“Patients may feel frustrated, anxious, even discouraged, because it can take weeks to months to understand whether the medication works,” says Dr. Myasoedova. “Some may feel overwhelmed by how many options there are and the idea that nothing may work.”

That’s why Mayo Clinic investigators like Dr. Myasoedova are back on the case, finding ways to utilize pharmaco- genomics and artificial intelligence (AI) to get patients more quickly connected to the correct RA treatment.

In 2019, Dr. Myasoedova partnered with researchers from Mayo Clinic’s Center for Individualized Medicine to develop a model to predict patient response to the DMARD methotrexate by applying machine learning methods to patients’ clinical and genomic data.

The team recently incorporated generative AI into their model in order to dig deeper into patient genomics. Generative AI allows the model to read genetic sequences as text with contextual meaning — rather than researchers reading the genetic features and providing the model with their interpretation.

“This provides us with an ability to understand genetic data beyond the traditional information that has been derived from genes or variants,” Dr. Myasoedova says, ideally providing more precise DMARD predictions and helping to solve individual patient medication mysteries.

Like cortisone, this work has implications far beyond rheumatology; the team is collaborating with other specialties within the Department of Medicine to apply this same generative AI-powered approach to better predict treatment responses in other diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease and cancer.

Dr. Myasoedova’s work is one example within the division’s strong portfolio of active research programs, Dr. Davis says, and research is just one element of the division’s impact. From the days of Dr. Hench up to today, the division has also been a key contributor to rheumatology education and clinical practice in the U.S.

“We have been a beacon of hope and healing for generations of patients with rheumatic diseases dating back to the 1920s,” says Dr. Davis. “We have trained more than 200 rheumatology fellows who have then gone on to populate private practices and academic centers across the U.S. and beyond.

“I want to ensure that we’re moving forward and not only sustaining that legacy but trying to blaze the path forward and achieve great things.”

Read more about the 100-year history of Mayo Clinic rheumatology here.

This story appears in the latest issue of Mayo Clinic Alumni magazine. You can read or download a PDF of the issue here.

Mayo Clinic alumni are entitled to the print version of the quarterly magazine. If you’re not receiving the magazine, register or log in to your online MCAA profile to make sure your address is correctly entered. Or contact the Alumni Association at mayoalumni@mayo.edu or 507-284-2317 for help.

Photography credits:

All historical images and documents: Mayo Clinic Archives

Evidence board: Michael Burrows

Eric Matteson, M.D., Gene Hunder, M.D.: Tony Pagel

John Davis III, M.D.: Taylor Parker

Edward Kendall, Ph.D.: Mayo Clinic Archives/Associated Press

Cortisone bottle: Paul Flessland

Elena Myasoedova, M.D., Ph.D.: Taylor Parker