Revisiting the Class of 1976

Originally published in Mayo Alumni, Fall 1993.

ON NOV. 12, 1971, Atherton Bean, then chair of Mayo’s Board of Trustees, announced Mayo would open a four-year undergraduate medical school in September 1972. The historic significance of the day added to the drama at Balfour Hall, jammed to capacity with reporters, Mayo officials and community supporters.

Long and careful deliberations spanning some five years preceded that September opening day when the school finally became a reality.

The late Dr. Raymond Pruitt, the school’s visionary, was named the first dean and given the honor –– and task –– of starting the school. One of Dr. Pruitt’s charges was to help recruit the first class of 40 students.

More than 20 years later, many of those students still hold fond memories of their years at Mayo, evidenced in recent correspondence with eight of those first-class members.

Mayo Alumni writer Beverly Smith-Patterson recently corresponded with class members to learn what they’re doing and what they think about medical education then and now. She also asked for their medical school stories, a few of which will have to wait for retelling in person!

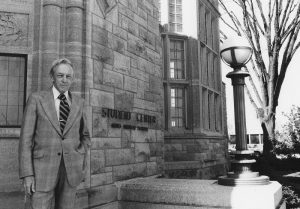

Following are the alumni who wrote: Drs. Brad Bringgold, family practitioner with Kodiak Island Medical Associates, Kodiak Alaska; Rob Bruley, family medicine physician in Watkins, Minn.; James Davison, ophthalmologist with Wolfe Clinic, P.C., Marshalltown, Iowa; Eric Evenson, occupational health consultant to the Surgeon General of the U.S. Army, Falls Church, Va.; Joyce Jones, internist with General Hospital, Washington, D.C.; Carol Juergens, internist with Kodiak Island Medical Associates, Kodiak, Alaska; David Kispert, radiologist with St. Paul Radiology, St. Paul, Minn.; and Doug Martin, pediatrician and infectious disease specialist with Park Nicollet Medical Center, Minneapolis, Minn.

The first class of a school creates an impression and a tradition simply by being first. What contributions do you think your class made?

Dr. Rob Bruley: What can I say? Horror? Joy? Confusion? Humor? Psychosis? A reaction-formation toward more conservative classes subsequently? All these would seem to be among our “contributions.”

Basically, I think we provided a unique perspective from which medical school approaches and practices could be honed and refined. We were the guinea pigs on whom the inevitable bugs could be worked out. Because were rather individualist (yet also a close-knit class) and receptive to change, new ideas, and the unknown and not shy about providing sometimes overly honest feedback, I think we were more than appropriate as a pioneer class.

Dr. Carol Juergens: I believe our class was picked to be diverse and turned out to be a little more independent-minded than was expected –– to the point of becoming “notorious.”

We were tail-end products of the ‘60s whom Mayo had not experienced in depth in the form of students. Our long hair and casual dress in the classroom were disconcerting to many, as was the case of beer someone brought to an evening meeting in the Harwick Building!

We became close-knit and remained egalitarian, refusing to form a chapter of Alpha Omega Alpha, forming instead our own informal “A.O.K.” An adjustment period to us students was inevitable. The character of our class found Mayo jumping into undergraduate medical education with both feet before it was quite ready. Mayo seemed shy, tenuous, eager. We were eager but vocal, and maybe contentious. We had no dearth of commentary about what worked and what did not, probably seeming impolite by Mayo standards.

Nonetheless, Mayo encouraged our input about instructional methods, content and the balance between basic sciences and clinical medicine. I personally did a subinternship at an outside institution between my junior and senior years. When I returned, I felt more confident and assertive. Mayo “rose to the occasion” and I was allowed to participate more directly in patient care during my senior year than either Mayo or I anticipated. The process of being flexible was furthered.

How do you think medical school is different today?

Dr. Eric Evenson: My experience with medical school today is based on my teaching involvement with the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS), Bethesda, Md. Students at USUHS are active-duty military officers who incur a seven-year service obligation following medical school and residency.

Medical education today is no more demanding than 20 years ago, but it certainly is more high-tech (computers), and progress in medicine has increased the amount of material to learn. Medical ethics is a more important part of education now also.

The students themselves have changed. They appear more committed to medicine, obvious from the fact that they have incurred a 15-year service obligation –– four years of medical school, four years of residency training plus the additional seven-year commitment that I mentioned. This time investment allows them to have a much clearer idea of what they want to specialize in.

They seem more serious and less relaxed than our class. Repayment of medical school debts is not a concern for these USUHS students, but then they won’t make large incomes practicing medicine in the military. I also see a return to an emphasis on primary care and preventive medicine, which was prevalent in the ‘70s.

Dr. Joyce Jones: I think that Mayo Medical School was more progressive than a lot of medical schools at the time. Medical schools now spend more time discussing ethics and medico-legal aspects of medical care.

One major difference between medical school students today and our class is the general atmosphere in which medicine is now practiced. With the advent of AIDS, which is commonly seen in Washington, D.C., and the move to more bureaucratic meddling into the practice of medicine, I find more students turned off by internal medicine. Even though they like the internal medicine rotation, they cannot see themselves adopting it as a specialty.

What challenges do you face practicing in a remote place or small town? Why did you choose this setting?

Dr. James Davison: Why indeed? My thinking on the matter is right. My perspective is slightly different. I wanted to raise my family in a town about the size I was raised in –– La Crosse, Wis., with a population about 50,000. I wanted to move to either California or be in the Midwest, and the Midwest won primarily so we could be close to the family.

The thing that attracted me to Marshalltown was the practice opportunity. I joined six other people who were good scientists, honest clinicians, kind and generous. Believe it or not, this combination is very difficult to find in one person much less six.

Marshalltown is fairly close to Des Moines so we have been able to do some of things that are done in the “big city” while avoiding some of the problems that city life brings with it.

My love for people from Iowa came from my experience at Mayo. We saw patients from every state in the union and may countries, but the patients from Iowa were always the nicest.

I continue to be happy with my choice. It has been great for my family and has been a good career for me.

When you graduated, where did you think you would be? Is that place different from where you are?

Dr. Brad Bringgold: I am practicing general medicine in a small town, which is what I imagined I would be doing. I thought the practice would be in Montana, but I’m in Alaska after a few years in Arizona. The challenges are basically the

same as anywhere: information management, personal relationships and balancing the various demands on one’s time. Here I am more obliged to figure things out on my own, and I like that. I am proud of the job I do and enjoy the work immensely. I hope my classmates are having as good a time.

Update us on your work and your future plans.

Dr. Rob Bruley: I’m doing a somewhat unique form of outpatient family medicine, happily free of obstetrics and surgery, in the delightful little community of Watkins, Minn., population 840. It is roughly 80 miles west of Minneapolis, which is where I live.

I work three days a week, stay overnight on Monday and commuting [sic] the remainder of the time. The neighboring physicians and community facilities have been more than gracious in providing back-up care and I, in turn, provide referrals. The local people are fantastic, positive, humorous, even exuberant –– and quite feisty and unaffected.

The agriculturally based area is a real plus. I feel much more in touch with the natural rhythms of life, preferring fresh air, foxes and pheasants to billboards and traffic.

I have discovered the true joys of caring for elderly people and nursing home residents as well –– somewhat, I must admit, to my surprise. And still, I always have the option of taking periods of time off, as when I returned to French Polynesia for a month this winter. Of course, I don’t get paid during the times I don’t work and I have definitely sacrificed financial rewards and security for this most enjoyable lifestyle. It has certainly been worth it.

In juxtaposition, but also in harmony with this practice style, is what I do the other two days of the week. I am a licensed wine broker representing perhaps a dozen wineries, mostly Californian, to on-and off-sale accounts. It, in fact, has become a standard joke with my patients that I do “the wine thing” because “the smells are better and I get to drink while I work.”

More seriously, I do find that the contrast of the two careers has been enormously enriching and stimulating. Each provides a respite from the other.

Finally, to add yet another variable, the most marvelous one, I have fallen in love with a very special woman and mother who is also in the wine business. We have become engaged and, thus, I anticipate future significant and powerful changes for this life-long, or so I thought, bachelor.

Dr. Joyce Jones: I received an M.P.H. degree in 1990 from George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and have since spent some time doing clinical research. I hope to be able to devote more time to research and continue as an academic physician.

What advances did you think medicine would make?

Dr. David Kispert: That was 17 years ago. I honestly have no idea what I thought would happen. On completing medical school, I thought they had made me learn just about everything I needed to know. Boy, was I wrong. The more you learn, the less you actually know.

Being a neuroradiologist, most of my experience is in medical imaging. Since 1976, the advancement in medical imaging has been phenomenal, and not only in morphologic imaging such as CT, US and MRI. The recent advances in functional imaging using MRA, MRS and PET are taking medical imaging in a new direction, with many new clinical and research applications. Advances made in the past 15 years have truly boggled my mind. Hopefully, the future will continue to surprise me.

If you were to do it over, would you go into medicine?

Dr. Rob Bruley: Up until several years ago, I could no have been sure how to respond to this question. I had tried a variety of practice styles and had never found something that clicked for me. Ditto for the locales. Certainly, traditional practice models and the incredible time demands involved had left me dissatisfied. Perhaps, selfishly as some would claim, I was unwilling to go through life exhausted and restricted from the ability to pursue extended travel and other interests. Life is too short and too rich.

Then in the fall of ’91, more or less by sheer luck, I found myself back doing what I originally had intended in medical school: pursuing rural family practice.

I was able to find a marvelous little community within extended commuting distance from the Twin Cities that accepted me and my practice preferences –– me exactly as I am, which is someone loving the country but wishing to live in the city; someone waning to essentially do part-time, outpatient general medicine; and someone needing to travel frequently, both for pleasure and in pursuit of another “full-time/part-time” career (wine).

To all this the town said “OK” with a smile. Since then it has seemed like a match made in heaven. Consequently, I love my medical career and would definitely do it again.

Dr. Doug Martin: Although I suspect that none of us are doing exactly what we envisioned 20 years ago, some of the lures of medical practice continue.

It seems like we spend more of our time in business, administration and politics. But patient care brings us back quickly to the human side of the profession.

When seeing patients, a day doesn’t go by without the opportunity to share someone’s, often a virtual stranger’s, problems or concerns and hopefully help them feel better. That level of trust is a true honor. Of course, I’d do it all again.

Reminiscences

Dr. Doug Martin: Picture a cold, gloomy Saturday morning in November and a first-year Mayo medical student sitting in a make-shift classroom on the 14th floor of the Plummer Building, struggling with basic neuroscience. Why is it so hard to remember where these tracts go? Why is it so hard to remember what messages they carry and which way? Worst of all, thoughts of “what does it matter?” enter my head.

Smart, kind but stern Dr. Jerry Chutkow pauses beside my table as class is ending, points at me and says for all to hear, “About this last quiz … I want to see YOU after class.” Other members of my small group file out, while I am left fighting waves of anxiety and nausea.

Doubtless Dr. Chutkow is right, I’m thinking. I can’t even spell “decussate,” much less know where it happens. I may as well forget medicine, it’s just too hard for me. The room is clear. Dr. Chutkow approaches.

“Mr. McCoy,” he says, “your performance on the last quiz was not up to my expectations. I want you to feel free to come to me for help after class if you have special questions.”

My heart leaps! Dr. Chutkow has confused me with Charlie McCoy! I was so relieved. I don’t think I ever told Dr. Chutkow his mistake. And despite that poor quiz performance, Charlie McCoy and I are now partners, both at a clinic where we have strong support from qualified neurologists.

Dr. Brad Bringgold: Thank you for an opportunity to share some of Dr. WInthrow’s personal history with our alumni colleagues. (The two are ’76 classmates and, together with alumna Carol Juergens, practice in Alaska at what they call “the little Mayo of the North.”)

Luck and brute strength have saved him from nature and himself more times than I can recall. He has hiked through the Texas desert without water and grown his hair out at Mayo, which possibly makes him brave. He has survived jumping from a falling tree to a nearby tree with his chain saw [sic] still hot, swimming in the Gulf of Alaska after his skiff sunk, being rescued by Coast Guard once and searched for when overdue on four other occasions.

While this illustrates he is hard to kill, behaviors during medical school –– like bashing in the roof of my ’57 Lincoln and then kicking it back into shape from inside –– make me want to kill him. Somehow, however, it’s hard to hate him. He is a good guy and a good doctor in spite of his idiosyncrasies.

Dr. Eric Evenson: During the first or second week of our first year, some members of my gross pathology section (myself, Jim Davison and several others) decided to forego our participation in Dr. Robert Bahn’s late afternoon tissue review following the day’s autopsies. We reprioritized our activities and determined that oral rehydration at the Happy Warrior Lounge (now gone) was more appropriate.

After a half hour or 45 minutes (and several beers), I received the first “page” of my medical career. Dr. Bahn had determined that his gross tissue review had precedence over the Happy Warrior Lounge, and we were instructed to return to the Medical Sciences Building. Our experience at the Happy Warrior somewhat altered (clouded?) our perception and appreciation of the gross specimens!

Dr. Joyce Jones: Medical students still know how to have those “light” moments. I remember a group of us photocopying our faces and pasting the pictures on the wall of the student center. I still can’t believe we did ti!

Dr. David Kispert: While observing a procto exam, the proctologist turned to me upon finding and removing a polyp from the patient and asked, “Would you like to take a look?” The patient, not knowing I was in the room responded, “No thanks, let’s just get this over with.”

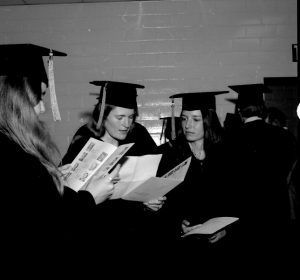

The birth of a tradition

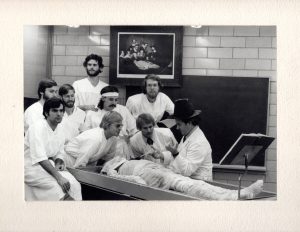

Re-enacting Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson

“It hung on the wall in the laboratory and looked down on us every day of that first session,” recalls Dr. Duane Rorie, the first professor of gross anatomy at Mayo Medical School. “The students thought it would be fun to re-enact the pose for a photograph and the tradition of re-enacting Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson painting was born.” Of course, the medical students, enlightened by the ages’ accumulated knowledge of human anatomy, corrected the anatomical error of the less advantaged 17th-century Dutch painter. No doubt the master of the paint brush naively painted the muscles of the arm in reverse position.

Error notwithstanding, the posing tradition became an annual event that brought all the gross anatomy students together. Dr. Rorie remembers the resourcefulness of some students who “went to the Harwick cafeteria and found large coffee filters, which we slipped over our heads to serve as the white collars seen in the original Rembrandt.” The most recent photo of the Class of 1994, above, reveals today’s medical students are adding their own creative touches to their class portrait –– which now requires two groupings because of the larger course enrollment.

When Dr. Donald Cahill came to the classroom in 1980 as the new professor of gross anatomy, he was pleased to see how much the tradition meant to the students. “They wouldn’t let a gross anatomy class pass without having it done,” he says. He is the “lesson subject” in the current portrait.

Almost 20 photographs line the wall of the laboratory today. Each contains vivid memories for students and faculty alike. “The group of pictures attracts a lot of attention,” says Dr. Cahill. “Nearly every visitor, after a quick look around the room, begins to gaze at them.”

–– Andrea Johnson

Read more about the class of ’76:

Additional memories from class members in 2017: https://alumniassociation.mayo.edu/memories-class-1976/

Story published at time of graduation in 1976: https://alumniassociation.mayo.edu/mayo-clinic-school-of-medicine-class-of-1976/

Update on the class of 1976, published in 1983: https://alumniassociation.mayo.edu/charter-class-update-first-mayo-medical-school-graduates/