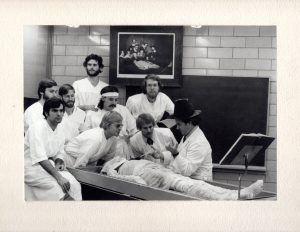

Mayo Clinic School of Medicine class of 1976

Class of ’76

by Donald L. Deye, member, class of ’76, Mayo Clinic School of Medicine

originally published in 1976 in Mayo Alumnus magazine

“MAYO CLINIC PLANS Medical School . . . Med School Slated for Rochester. . . . And Now, A Mayo Medical School” headlines and articles filtered their way through the postal system to me from relatives back home in Minnesota. This news was of more than passing interest to a Minnesota-born premed. Mayo Clinic had touched the lives of my family in many ways through the years, and the thought of studying medicine there was a bit awesome. Inquiries were sent, forms filled out, and an interview was requested to coincide with my trip home for Christmas.

“Don’t count on our starting in ’72. We’re accepting applications more on the strength of positive thinking than finalized decisions. Yes, there will be a medical school here. The question is, will it begin this fall or next?” That was the gist of the initial response to application requests. Thus, most of us also filled out the U of M’s MMPI forms and fumbled with responses to awkward questions concerning things personal and sexual. (It was considered reasonable to apply to at least eight medical schools at that time; I still shake my head when I think of struggling through all of those application forms.)

I’m sure each of us remembers when we were at the time we learned of acceptance into the new Mayo Medical School. It was New Year’s Day, 1972. I had hitchhiked from Winona, Minnesota, to Kenney Airport and my discount charter flight for a long-anticipated German Studies Semester was now 16 hours past announced departure time, grounded for mechanical reasons. At 3 a.m. I decided to give one last call back home. Months’ sustained tension burst out of me with a great WHOOP! as news of acceptance was relayed.

September 5, 1972: Smiling and nervous, 40 new students milled about the lobby of Med Sci. We were a diverse group, we learned. Ages ranged from the teens into the thirties. Academic background ranged from three years’ college to Ph.D.s. Political preferences, philosophical leanings and lifestyles ran the spectra. Yet we became close during that first year. Eleven months of intensive classroom exposure to mountains of materia medica helped develop a common identity.

We were unique in the Mayo institutions at that time. The fact that our mentors and the institutions were having us as their first students in this setting made them unusually solicitous of our advice and feedback. This attitude made them more approachable and the milieu less threatening. Not only were we given evaluation forms after each segment of the curriculum and regularly scheduled meetings with the administration to ventilate unforeseen frustrations, but we were also divided into “T” groups of four students each, with both a staff physician and resident assigned to each group. These small groups were used as a backup system for student feedback, and also as basic psychological support/anxiety verbalization areas. They really cared about how we were doing, one sensed.

Clinical medicine was heavily emphasized in our curriculum, despite the fact that half of the third year was slated for laboratory and research pursuits. The first year was a concentrated didactic dish of preclinical basic sciences leavened at intervals with Dr. J. M. Kiely’s Introduction to the Patient series. A frequently encountered problem during this first time around was that instructors were, at times, unsure of our relative level of medical sophistication. Some first-year lectures went into such details as specific drug dosages and the amino acid sequences of globin; others rehashed, in an introductory manner, material previously covered.

The physical locus of instruction changed several times during the first year. This present Student Center was still the former Rochester Public Library. Classes began at Mann Hall for the intensive month of Introduction to Structure organized by Drs. A. L. Brown and J. L. Titus. Meanwhile, the fourteenth floor of Plummer Building was cleared and study carrels, projectors, blackboards, teaching models and other instructional materials were assembled there. High ceilings, ornate architecture and a superlative view characterized our environment once the move was made to Plummer Fourteen. But it became rapidly apparent that the room was not acoustically designed for lectures, a problem that was lessened somewhat when a platform was installed for speakers to use a la Hyde Park. That winter we made yet another move into the newly remodeled Student Center Building, which was to become the school’s permanent home. (Instructors still had to raise their voices, however. This time it was in order to be heard above the sounds of construction as the Hilton and Guggenheim buildings went up around the Student Center.)

Perhaps we were closest as a class during that first year. That was the only year we were together as a unit for prolonged periods. Later our common experience would lessen as our directions diverged academically. We felt a bit like very fortunate guinea pigs. We were a small enough class that we felt comfortable making decisions as a group and decided against electing any class officers. Having arrived in medical school via the competitive academic grind of premed GPA and MCAT games, we eschewed intraclass competition and decided against establishing a local AOA chapter.

While the first two years were structured as a core curriculum which we would all experience, the last two were designed for maximum flexibility for pursuit of individual interests. Year Two was heavy with clinical content and included rotations in medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics/gynecology and surgery. Also included were brief off-campus assignments with family medicine preceptors in rural settings and a Mayo modification of the U of M’s human sexuality “blue movie” immersion. The bulk of this year’s instruction was one-on-one with staff physicians. Only one afternoon per week was used for group didactic purposes . . . this in pharmacology and laboratory medicine.

Patient exposure in an adequately supervised atmosphere characterized Year Two. We observed seasoned clinicians taking histories and performing physical examinations, attempted to emulate them and presented our workups to them. The atmosphere of this individualized interaction was decidedly nonthreatening, yet intensely instructive.

The clinical half of Year Three was a logical extension of the clinical rotations of Year Two, consisting of six weeks of medicine and several shorter clinical rotations through medical specialties. Response to this set of experiences was also strongly positive, for the most part. Some of us went to national conventions of medical students and learned how unique and fortunate our situation was. Other students complained of depersonalization and scut work. I had to ask my cohorts from other institutions what the meant by “scut,” both the expression and the experience having not been a part of my experience at Mayo. After Year One, the bulk of our clinical instruction was in the highly motivated one-on-one setting.

The laboratory half of Year Three was a chancy thing.

Roughly half of the class went the pathology/anatomy route. This was probably the best-structured rotation we were offered at the time, and some felt that we had somehow missed out on a frequently referred to facet of medical education in the past: the year with the cadaver. The path/anat elective allowed many to fill in this perceived gap. Others did research assignments of various types, including population studies, studies on atheromatous plaques in pigeons, and human urinary melatonin excretion patterns. While some felt this time could have been better used, others felt fortunate with the outcome of the time gamble which research always represents.

Year Four included a required rotation through Medicine Four where the medical student was given opportunity to function as he/she would later in his/her career: caring for assigned patients, doing hospital workups and writing orders. While all actions were reviewed for appropriateness and efficacy, autonomy was encouraged.

The rest of Year Four was elective time, with many excellent in-house rotations offered in every field of clinical endeavor. Most students also availed themselves of the opportunity to experience off-campus assignments during this period. A very popular rotation was the trauma service at San Francisco General, chosen to complement with acute care the largely tertiary care nature of much of Mayo’s practice.

The patient has always come first at Mayo Clinic, and continues to do so without compromise. This means that students here do not have the degree of unsupervised responsibility and hands-on procedural experiences that may characterize the experiences of cohorts elsewhere. We are immersed in a rich clinical environment and given ubiquitous excellence in our role models, however.

Where are we going as individuals from Mayo’s Charter Class? Over half of our class has matched to primary care residency programs (23 of 39 students). This is surprising to some observers, in view of the tertiary care subspecialty strengths of the Mayo institutions. Yet the early development of the medical school included this sort of primary care emphasis as a goal, stated in writing.

Twenty-two class members will remain in Minnesota, four will study in California, two each in Illinois, Wisconsin and the military, and one each in D.C., Indiana, Iowa, Nebraska, Texas and Washington.

It’s been a most interesting beginning, both for members of the class and for the school. We students are grateful and honored.

Read more about the class of ’76:

Additional memories from class members in 2017: https://alumniassociation.mayo.edu/memories-class-1976/

Update on the class of 1976, published in 1983: https://alumniassociation.mayo.edu/charter-class-update-first-mayo-medical-school-graduates/

Revisiting the class of 1976, published in 1993: https://alumniassociation.mayo.edu/revisiting-mayo-medical-class-1976/

Mayo Clinic School of Medicine class of 1976

The data following each graduate’s name indicate undergraduate school, specialty interest, and residency training program.ˆ

Mark A. Arnesen

Carleton College

Pathology

University of Washington

Affiliated Hospitals

Bradley A. Bringgold

Johns Hopkins University

Family Practice

University of Minnesota Hospitals

Robert W. Bruley, Jr.

University of Minnesota

Psychiatry

University of California (Davis)

Affiliated Hospitals

Penelope J. Butler

University of Minnesota

Internal Medicine

Mayo Graduate School of Medicine

Jeffrey C. Cassel

University of Minnesota

Family Practice

USAF Medical Center

Wright-Patterson AFB

Barbara C. Chamberlin

Drake University

Internal Medicine

Mayo Graduate School of Medicine

Barry L. Cosens

Ohio State University

Psychiatry

Mayo Graduate School of Medicine

David R. Daugherty

College of William and Mary

Surgery

Mayo Graduate School of Medicine

James A. Davison

University of Minnesota

Ophthalmology

Los Angeles County––USC Medical Center

Donald L. Deye

Valparaiso University

Internal Medicine

Mayo Graduate School of Medicine

Eric T. Evenson

Luther College

Family Practice

Martin Army Hospital

Fort Benning

Christopher S. Fletcher

Stanford University

Family Practice

University of California (Davis)

Affiliated Hospitals

Kevin J. Flynn

College of St. Thomas

Pathology

Baylor College of Medicine

Affiliated Hospitals

Harvey B. Friedenson

University of Minnesota

Obstetrics & Gynecology

Mayo Graduate School of Medicine

Thomas G. Frisby

Winona State University

Family Practice

Mayo Graduate School of Medicine

St. Francis-LaCrosse

Herbert E. Gladen

University of Minnesota

Surgery

Mayo Graduate School of Medicine

Mark D. Hauge

University of Minnesota

Internal Medicine

University of Minnesota Hospitals

Joyce Jones

Memphis State University

Internal Medicine

District of Columbia General Hospital

Carol L. Juergens

Stanform University

Internal Medicine

University of Minnesota

Hennepin County General Hospital

Philip D. Kath

University of Minnesota

Internal Medicine

Cleveland Clinic Hospital

James W. Keane

College of St. Thomas

Family Practice

University of Minnesota Hospitals

Barbara O. Kimbrough

Iowa State University

Ophthalmology

Mayo Graduate School of Medicine

Stephen M. Kimbrough

Northwestern University

Neurology

Mayo Graduate School of Medicine

David B. Kispert

University of Minnesota

Diagnostic Radiology

Mayo Graduate School of Medicine

David A. Lundberg

St. Cloud State University

Family Practice

Mayo Graduate School of Medicine

St. Francis-LaCrosse

Douglas M. Martin

Macalester College

Pediatrics

Mayo Graduate School of Medicine

Charles E. McCoy

University of Minnesota

Family Practice

University of Minnesota

St. Paul Ramsey Hospital

Donald M. Molenaar

University of Minnesota

Internal Medicine

Northwestern University

McGaw Medical Center

John B. Mulvehill

University of Notre Dame

Surgery

Northwestern University

McGaw Medical Center

Jeffrey L. Nelson

University of Minnesota

Internal Medicine

Mayo Graduate School of Medicine

Kerry D. Olsen

Northwestern University

Otolaryngology

Mayo Graduate School of Medicine

Darryl R. Quiram

Mankato State University

Family Practice

University of Nebraska Affiliated Hospitals

Glenn M. Riewe

St. Olaf College

Internal Medicine

Mayo Graduate School of Medicine

Paul W. Schultz

University of Minnesota

Surgery

University of Minnesota Hospitals

Jeffrey J. Smith

St. Mary’s College

Pediatrics

University of Minnesota Hospitals

Randolph C. Steer

University of Minnesota

Pathology

University of Minnesota Hospitals

Joseph H. Tashjian

University of Minnesota

Diagnostic Radiology

University of Indiana Medical Center

Pamela W. Wallace

University of Minnesota

Psychiatry

Mayo Graduate School of Medicine

Mark E. Withrow

Iowa State University

Internal Medicine

Pacific Medical Center

Presbyterian Hospital